Metacritic launched in 2001, founded by Marc Doyle, his sister Julie Doyle Roberts, and Doyle’s old law school classmate Jason Dietz. Yes, that’s right, Metacritic was made by lawyers.

“I was a lawyer for a very short time,” explains Doyle. “Neither Jason nor I probably envisioned a long career in law. It was kind of like, Okay, this is a good background to have for whatever we want to do.”

“I went […] into a law firm for a few years, and then went into education, non-profit, and then eventually started with Metacritic. But I recognised immediately that Jason was a guy that if he ever came up with any idea, any business idea, I would want to be in business with him, because he was brilliant.”

Dietz – an early web enthusiast who introduced Doyle to email and Netscape – dreamed up the idea of Metacritic. Doyle says it was founded on the notion of saving people money, with the thinking that pooling together all of the reviews from the most noted critics might be a reliable indicator of quality.

“As I get older, I realise now it’s about time,” he adds. “It’s like, do you want to invest all this time in this TV show which is going to peter out by the third season?”

The site was bought by CNET in 2005, and since then it has had various owners. Most recently, in 2022, it was bought by Fandom, along with sites like GameSpot and GameFAQs. But little has changed behind the scenes – and it remains a fairly small operation.

“You have product people that manage multiple sites, you have engineers that service multiple sites, same with sales people,” says Doyle. “But just editorial-wise, in my little team there’s five people.”

Bonuses

There has been lively debate down the years over Metacritic’s role in the game business. Perhaps most controversially, some companies have tied bonuses to a game’s Metacritic score. Famously, the developers of Fallout: New Vegas missed out on a bonus after the game scored 84, rather than the targeted 85.

Doyle emphasises that Metacritic isn’t involved in any of this. “I guess early on, it was kind of flattering that someone would have enough faith in our system that they would judge the quality of their developers based on this, but really, we are solely focused on our users and helping them have a better gaming experience.”

Still, given that people’s livelihoods can sometimes depend on a good score, does he feel any responsibility for that?

“No, no way,” he says. “As long as we’re being honest and we’re being credible about what we do, then I sleep well.”

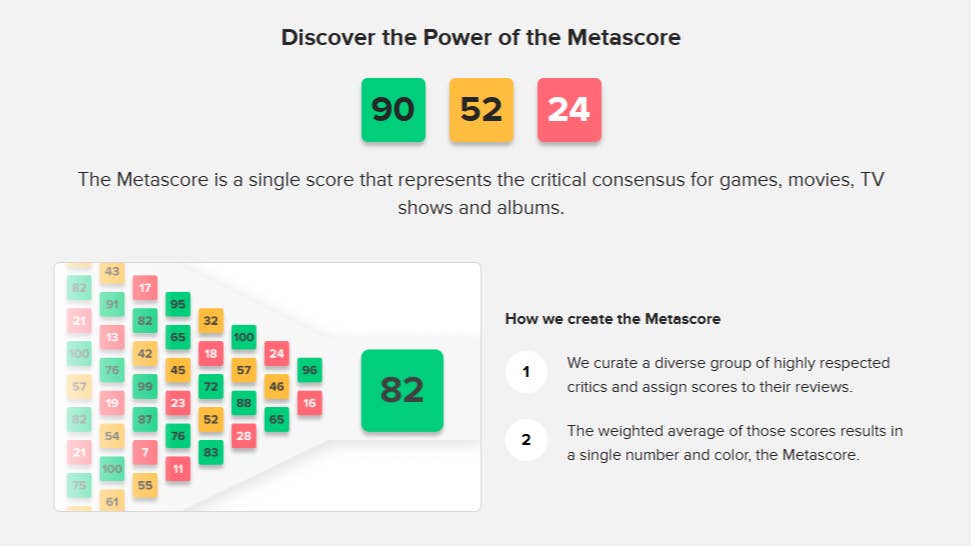

The Metascore

There have been tweaks to Metacritic’s system in the past 24 years. Originally, reviews for the PC and console versions of a game were lumped together into a single score, until the PC gaming community complained, says Doyle, prompting them to separate the scores by system.

“It is important to me, because there are clearly differences between versions,” he says. “So […] we’ve separated that out, and that’s worked beautifully.”

Metacritic converts review scores into a 100-point scale. “So if it’s two and a half out of five, we make it a 50,” says Doyle. The only controversial element, he says, is converting letter-based scores, like ‘F’. “Should that be a zero, or should it be 58 like it is in American schools?”

He says that when Metacritic onboards sites that score using letters, he has to explain that Metacritic scores C as 50, F as zero and AA+ as 100. “We just do our best to make it as intuitive as possible.”

Score weighting

There is a bit of tinkering, though, to reach that final Metacritic score. “We do have slight weightings to our publications,” says Doyle. A review from a publication staffed by veteran writers “might be worth a little bit more in the overall average”, he says. “We always have done that.”

But he adds that the weighting is subtle, and an unweighted score would only differ by “maybe a point or two” from the final Metacritic score. “So it doesn’t have a radical impact on our final numbers, but we do give a little bit more influence to the highly respected veteran critics.”

He won’t reveal which critics or publications are worth more than others, however, and what kinds of calculations go on behind the scenes. “It really is our secret sauce.”

But he will say that a study that claimed to reveal Metacritic’s rating system was not correct. “Like, Giant Bomb was at the very bottom,” he recalls. “I think I had to call up Jeff Gerstmann, one of those guys, and I’m like, ‘Guys, I hope you know this is not accurate’.”

One and done

Metacritic has a strict policy of only allowing a publication’s original review to count towards a game’s Metascore. There are no do-overs.

Doyle says this is to avoid score manipulation. Back in the early 2010s, he says, “I had certain PR folks just hounding me.” He recalls one occasion when he got “10 or 15 emails” demanding him to remove a certain review and delist the critic, “and then ultimately change the score”.

He adds that sites were sometimes pressured by “outside forces” to raise the score on a review. “That used to be prevalent in the 2005, 2006, 2007 era.”

“Your first published final score will be the score that Metacritic goes with, and we will not change it”

Marc Doyle, Metacritic

“You’d have a certain big game from a big publisher, and the first review score would be C+. And then within three hours, they’d pull down that review and they would say, ‘Sorry, this didn’t rise to the level of our editorial standards’. And then two days later it goes back up as a B or a B+.”

“What’s happening here? Well, people came to me, whistleblowers, whatever you want to say, and [said], ‘Oh yeah, we were pressured here. This was not a good situation’. And so ultimately – and again, this was happening monthly, maybe weekly at a certain point – I decided I’m going to start backstopping these critics. I’m going to protect these critics and say your first published final score will be the score that Metacritic goes with, and we will not change it.”

Re-review policy

But in an era when games are constantly evolving, some outlets are now re-evaluating games that have changed significantly. IGN, for example, introduced a policy in 2014 of re-reviewing games “when we feel our original recommendation is no longer reasonably accurate”.

Metacritic’s policy can leave games stuck with a rating that doesn’t necessarily reflect the game’s current status. No Man’s Sky, for example, transformed its Steam rating from ‘Overwhelmingly Negative’ to ‘Very Positive’ over the course of eight years. Yet the PC version is still lumbered with a Metascore of 61.

So, will Metacritic consider including re-reviews in its scores?

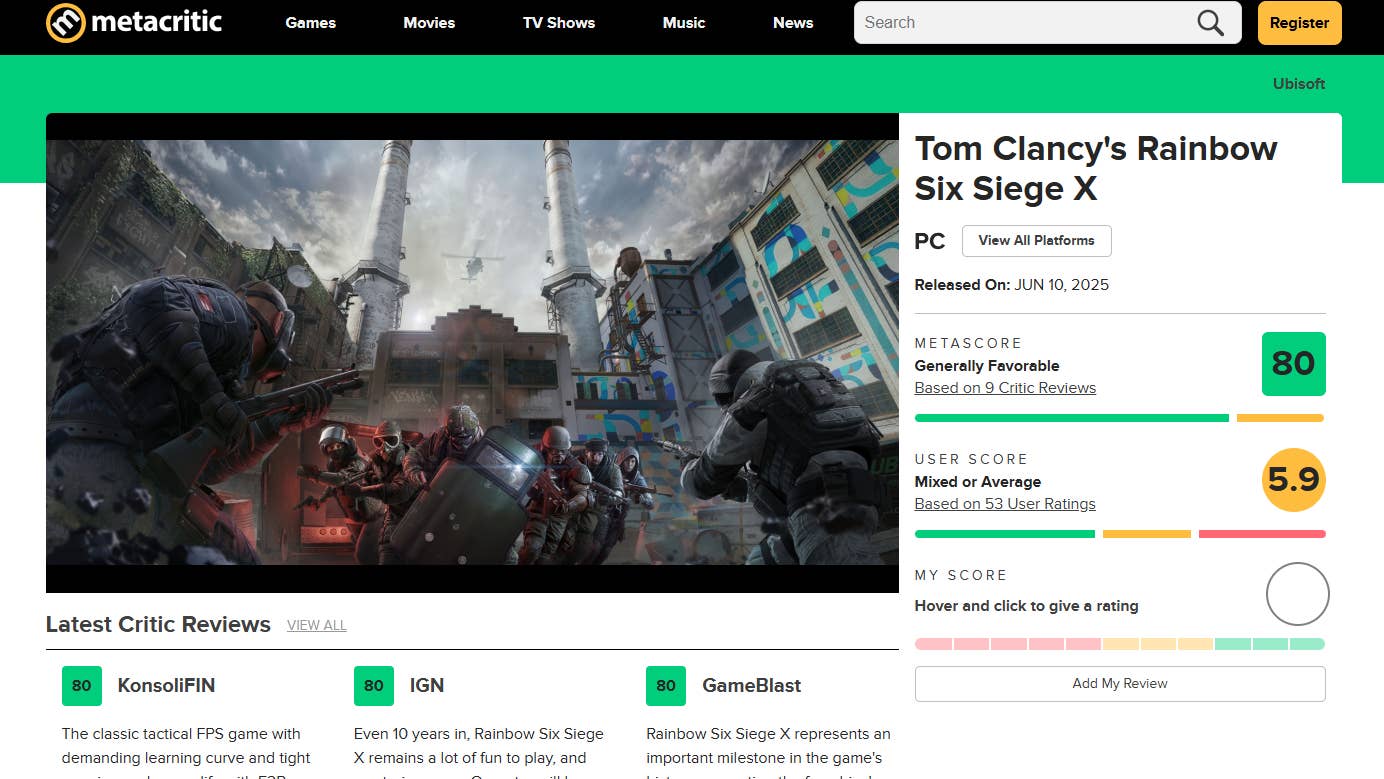

“We’ve thought about this a lot over the years,” says Doyle. If a game was re-released as a special edition, he says, perhaps including all of the DLC (like with Rainbow Six Siege X), “then we would create a separate page for that game, and we would have all those new reviews on that separate page, while preserving the original page, which has reviews from the release window.”

He thinks it’s important to keep a record of a game’s original reception. “I want to know what the top critics thought when that game came out.”

In any case, few outlets are likely to re-review games, he thinks. “The staffs are so small now on all these publications. Publications are going away. It’s become harder with certain search engines to even fuel traffic to your sites. So the thought that everybody has the resources to go and re-review a bunch of older games – it’s just not practical.”

Still, he’s open to the idea of including links to re-reviews on a game’s Metacritic page. “Like, ‘Hey, these are some reviews that have happened since the original release’, something like that.” He adds that Metacritic has value as a repository, a bucket of information about specific titles. “And as part of that bucket, we could have, like, future reviews or additional content related to this game. Yeah, absolutely, I can see that happening.”

“But in terms of changing their official score and changing the Metascore, I personally don’t think it makes sense.”

The critics

Occasionally, in the past, Doyle says some sites have asked not to be included on Metacritic. “I don’t want to speak for them, but there could be an added level of scrutiny that if you have a particularly high or particularly low score – probably low score – it might attract some heat from PR, development, publishers, all that kind of stuff, and they just didn’t want that heat.”

He’s happy to remove sites from Metacritic if they request it. But usually, it’s a case of people asking to be let in.

Doyle says he has an annual evaluation window, usually starting in January, when he decides which sites can be added to Metacritic’s roster. “If somebody writes in, I give them a questionnaire,” he says. “Thirty-seven questions asking about the site, the site’s history, the review rate. Tell me about your games editor-in-chief, their background, tell me about the writing staff, your scoring philosophy. You know, just a whole myriad of questions.”

“They get that back to me, and I go through and put it all in a spreadsheet, and analyse, and read a bunch of their reviews, and ultimately make a judgement call: would they be a good addition to the website?”

“If you don’t know what a low scoring game is, how can you define what the high scoring games are?”

Marc Doyle, Metacritic

One of the questions asks: ‘When was the last time you scored a game at the equivalent of 30 out of 100 or below?’

“And a lot of times they’re like, ‘Oh, never’,” he says. “And that just makes me think, number one, you haven’t reviewed a lot of games, or you’re only reviewing the shiniest of objects. I always feel like you’ve got to get your hands dirty: If you don’t know what a low scoring game is, how can you define what the high scoring games are?”

“Number two, there are going to be different types of critics that are tougher critics and ones that are more lenient. […] I think as long as they have internal scoring consistency, [and] they review a representative number of games, then it works fine in the Metacritic ecosystem.”

Who gets in?

Some decisions on who to include are easy, like when a respected reviewer leaves a publication to start a website of their own. “When Jeff Gerstmann originally left GameSpot and went on to found Giant Bomb, I added Giant Bomb’s first review to Metacritic, because I just knew he was one of the deans of the industry.”

But what about things like blogs? “Well, let’s just say this: if they’re, you know, 19 years old [and] this is their first review ever, they’re probably not gonna crack Metacritic right away.”

So, does it all just come down to Doyle’s subjective opinion?

“Well, I certainly rely on a group of advisors as well,” he says. These are critics from the publications that Metacritic tracks.

“You might think they would be incentivised to crap on everybody else from their area, but no: I’ve found that if you ask a legitimate question and you’ve built up trust, then they will tell you the truth. They want to maintain their credibility with us and with me, and so I usually get a pretty frank answer.”

The questionnaire also asks, ‘What’s the most glaring omission on Metacritic right now?’, and Doyle says he has picked up lots of sites through recommendations resulting from that question.

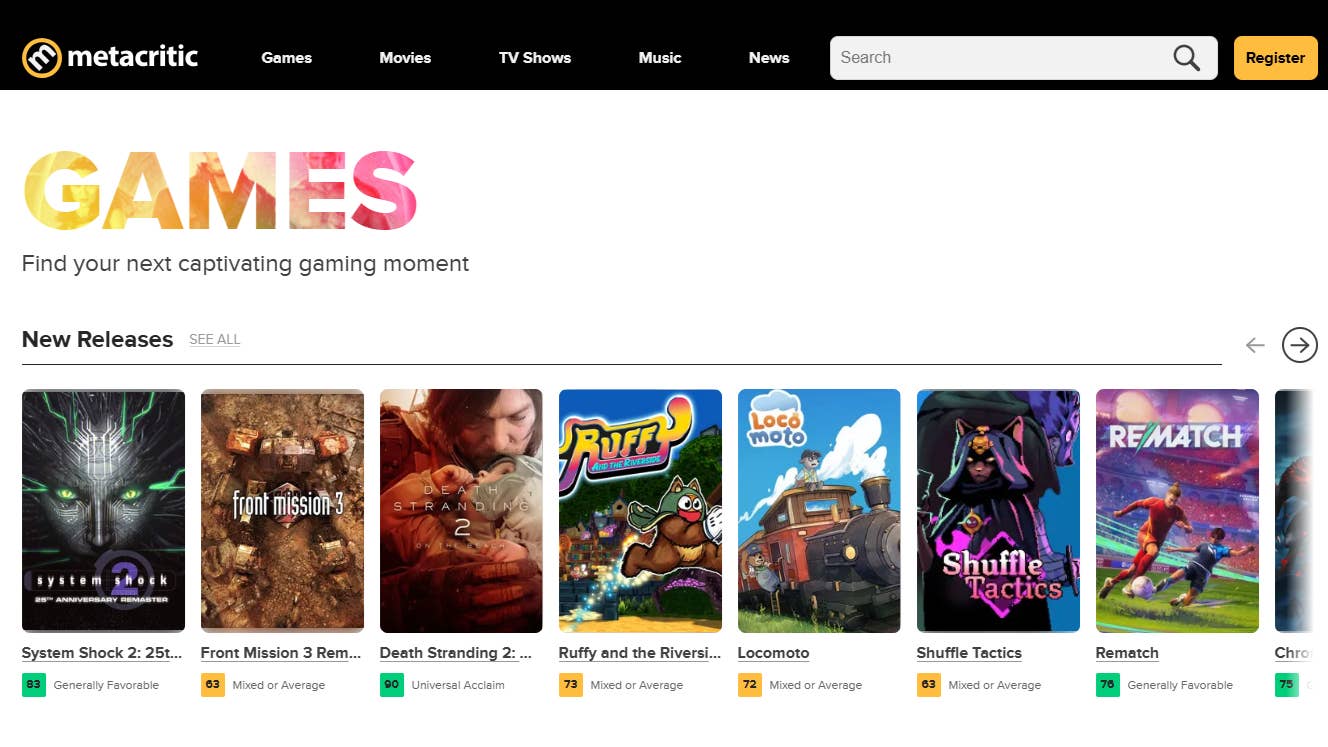

Metacritic is also more international now. “In the very early days, it was really just US-UK,” he says, “and then I think it was towards the late […] 2000s when we started adding people from overseas.”

But Doyle says he has to be wary of potential conflicts of interest when adding publications. “A recent change I’ve noticed is that you will have independent game fanatics, and they may work for or own their own PR agencies, and then they want to also have a gaming publication off to the side where they’re reviewing games – and so that gets a little murky.”

“I think we’re just at the beginning of trying to figure all that out, but I’ve always got to be extremely careful about how we tread those waters.”

Sites sometimes get downgraded, too. “For example, if you have a whole team of all-stars – like the Avengers of the video game critic community – and they all happen to leave and [the site brings] in a bunch of freelancers, that could have an effect on [the site’s] weighting, certainly.”

The future

The past couple of decades have seen the decline of traditional media and the rise of YouTubers, streamers, and podcasters – so is Doyle open to including non-traditional media like video reviews on Metacritic?

“I mean, we’re certainly open to it,” he says. “For example, Easy Allies, GameTrailers, their primary output was the video. What I asked of them was to give me a written component as well, maybe even something as minimal as a transcription, so that I could then use that for Metacritic. And they’ve done that.”

“I was a lawyer […], so I still believe in making an argument, giving a final score, giving evidence that’s leading up to your final thesis”

Marc Doyle, Metacritic

“It’s got to have a degree of the formal review format, whether it’s on video or transcribed,” he adds. “Because if you look back at my background, I was a lit major, I was a lawyer, all this, so I still believe in making an argument, giving a final score, giving evidence that’s leading up to your final thesis, all that kind of good stuff.”

“Call me old fashioned, but that’s really part of what we’re looking for.”

What about AI? Is he worried that it might replace the service Metacritic provides?

“I think, at least for now, you need humans somehow to inform the AI,” he says. “We’re going to continue to highlight those individual critics and publications that are doing the hard work. We’re going to continue to link to them, give them traffic, give them branding. They’re going to fuel our site. So it’s a mutually beneficial system.”

“Sure, you can say, ‘AI, should I play Grand Theft Auto 4, or this other game?’ And they might say, ‘Well, Metacritic says this, or Game Informer says this’.”

“Well, our mission has not changed, and will not change in that regard. We’re still going to take the top critics from around the world and come up with a critical consensus that we hope that the users can rely on. We’ll see if AI can replicate that. Who knows?”

“Throughout the years, we’ve had people take nibbles at us – like, ‘We want to make this totally engineering based, and we want to take the humans out of the cycle here’. And I knew that was problematic, too. You actually need human beings to make judgement calls throughout this process.”

At a time when AI is springing up everywhere, he says, “we still believe in ‘I'”.

“You’ve got to have that ‘I’ in there.”